July 17, 2019

How weather and market access issues set the stage for this year’s crop.

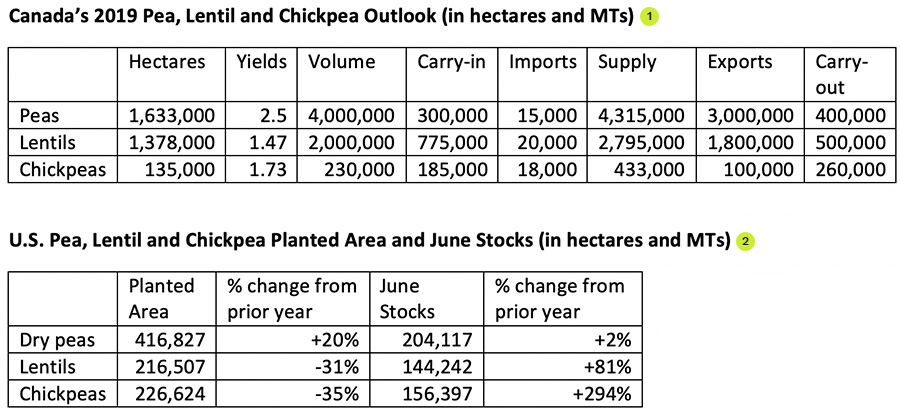

India’s tariffs on pulse imports have had a marked impact on North American planting decisions this year. The South Asian giant is the top destination for much of North America’s pulse exports, and with movement into that market stymied by steep import duties, inventories have piled up, especially in the case of chickpeas and lentils. The burdensome carryover has driven down prices for those pulse crops, and consequently the area seeded to them has fallen off.

In Canada, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s June Outlook for Principal Field Crops estimates the area seeded to chickpeas and lentils is down 25% and 10%, respectively. In the U.S., the USDA estimates decreases of 31% and 35% for lentils and chickpeas, respectively.

The dry pea area, however, is up this year. In Canada, a 12% increase is estimated, and in the U.S. a 20% increase is being reported. At the USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council, Todd Scholz, vice president of research and member services, suspects that, in the U.S. at least, some of the growers who shifted off of chickpeas ended up seeding dry peas, instead. Although the recent explosion in plant-protein food products may have had something to do with it, the main reason farmers stuck with pulses was likely because they have become fixtures in their rotations. Of course, low prices for other alternatives factored into their decisions, as well.

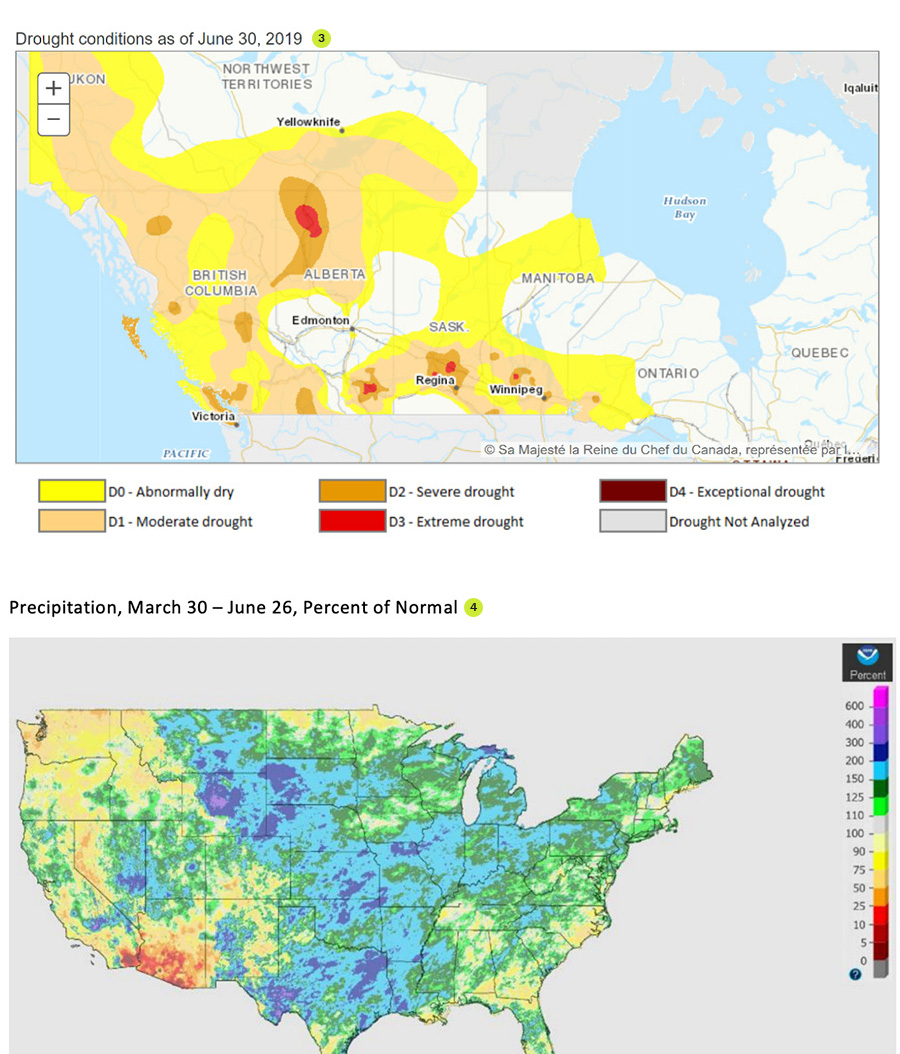

The 2019 growing season has been a challenging one for pulse growers in both Canada and the U.S., but for entirely opposite reasons. In Canada, dry conditions affected crop development, while in the U.S., surplus moisture delayed seeding and interfered with fieldwork.

With the harvest weeks away, GPC took a closer look at how these pulse crops are coming along in three major North American growing areas.

Western Canada

Canada’s pea and lentil production is concentrated almost entirely in the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, with Saskatchewan alone accounting for more than half of the nation’s pea area and more than 90% of its lentil area.

Quinton Stewart, president of the Canadian Special Crops Association, reports that most of the peas and lentils were planted about a month and a half ago under predominantly dry conditions. In the absence of bothersome rains, planting progressed fairly rapidly, running from late April through the month of May.

“Some areas didn’t see any rain until practically the last days of June if not the first part of July,” says Stewart.

June is an important month for crop development in the Canadian prairies, and the dry spell during that month is reflected in the limited height of the plants. Storms in late June into early July brought welcomed relief, however, and although the plants are not as tall as growers would like, Stewart remains optimistic about yields.

“Because of the lack of moisture early in the growing season, you have a lot of variability in the fields in terms of maturity and growth. In terms of crop condition ratings, roughly half the crop is good to excellent, and another good handful is below average to poor. Overall, I think we are on track for average yields.”

Looking at the breakdown by pea and lentil type, Stewart says that in a normal year, the green/yellow breakdown on peas is about 13/87. This year, he estimates green peas are up 20-30% compared to last year, while yellow peas, despite India’s import tariffs, are at least flat and even possibly up 5%.

“We did see good exports to China, and even some product making its way into the Indian market at various points of the year, as well as good demand from Bangladesh,” explains Stewart.

On red lentils, contrary to expectations of a dramatic drop off in response to the Indian tariffs, Stewart believes acres are down just 10% from last year, while green lentils are up 10-15% on attractive grower prices, especially for the Laird type. Stewart ballparks the red lentil area at 2 million acres and the Laird lentil area at 1.2 million acres.

Canada’s pea and lentil harvest is expected to begin around mid-August, with Alberta’s pea crop coming off the fields first. In Saskatchewan, the harvest should be in full swing by late August.

North Central United States

The two big pulse producing states in the U.S. Northern Plains are Montana and North Dakota. According to USDA NASS, dry pea plantings are up in both states compared to last year, while lentil plantings are down. For Montana, the 2019 dry pea area is estimated at 198,300 hectares, up 44% from the previous year, while lentil plantings are estimated at 129,500 hectares, down 36% from last year. In North Dakota, pea plantings are estimated at 163,900 hectares, up 8% from last year, and lentil plantings at 42,500 hectares, down 43% from last year.

Shannon Berndt, executive director of the Northern Pulse Growers Association, reports that wet conditions created some challenging seeding conditions this year, but nonetheless the crop went in the ground in a timely fashion for the most part. The wet weather has continued, but Berndt reports that despite all the moisture, the pulse crops seem to be doing well. Montana and North Dakota growers have told Berndt this is the best crop of pulses they have ever seen.

“We’ve had some cool weather as well, just at the right time, prior to anything flowering. So in some areas, there were prime conditions for pulses to really flourish,” says Berndt. “But with all the rain we’ve had in the region, disease is starting to show up, too.”

The North Central region’s pea crop is usually 70% yellow and 30% green. The lentil crop is primarily comprised of Richleas (65%), with some small green (25%) and red lentils (10%).

The wet conditions may delay the harvest. In Montana, growers are set to begin harvesting their pulses the first week of August. In North Dakota, it looks like the harvest may begin the second or third week in August.

Palouse Region of the United States

The Palouse region straddles the Washington/Idaho border and was the primary pea and lentil growing area in the U.S. until its output was surpassed by Montana in recent years.

Todd Schoz, vice president of research and member services at the USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council, expects that this year, the Palouse saw a significant drop in the chickpea area, a slight increase in the pea area and the same number of lentil acres as last year.

“I think this year there’s been a shift out of chickpeas into peas and perhaps into canola,” he says.

As in the North Central region, wet conditions slowed planting and put the crop three to four weeks behind schedule. In June, the weather was “very friendly to the bloom” as Scholz puts it.

“The bloom is usually nearly over by the first of July, so we’re still maybe a week or two behind, but the weather has been cool and generally favorable,” he says. “The pods are setting nicely and right now I’d say we’ll see some pretty good crops. Some of the chickpea plants are short because they were a little later than normal. The peas are also maybe not as tall as we’d like, but they’re setting pods and looking pretty good. And I’ve seen some pretty nice looking lentils. So we’re feeling optimistic. We think we are going to get average or better yields.”

The pea crop in the Palouse crop is almost exclusively of the green variety.

Thanks to the advantageous weather, the crop is making up for the late start and Scholz anticipates the pulse harvest will take place during the regular window, starting with the peas in late July and continuing into September for the chickpeas.

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.